Sons of Leitrim

Occupations and Comparison with Peers

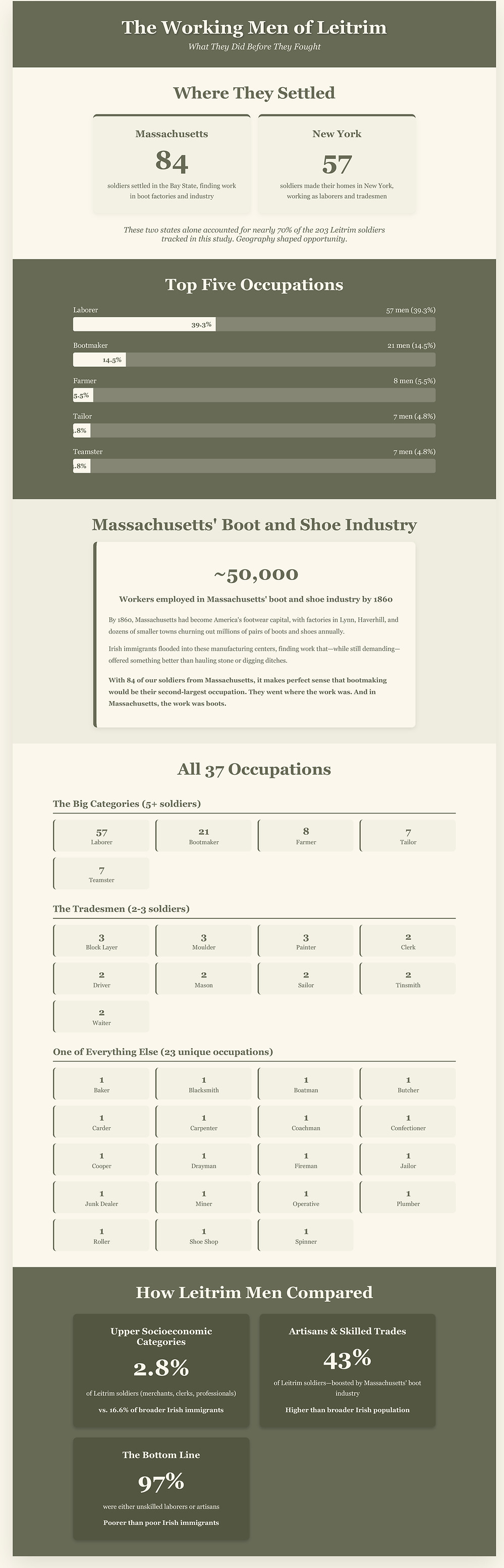

The Working Men of Leitrim: What They Did Before They Fought

From Leitrim's Fields to America's Battlefields

We know what 148 of our 196 Leitrim soldiers did for a living before they picked up rifles. Census records, enlistment forms, pension applications, and their own letters tell us they came from thirty-six different occupations—a surprisingly diverse array of trades and skills.

But here's what the numbers really tell us: these were working men. Hard-working men. Men who knew what it meant to labor with their hands.

Where They Settled, What They Did

Geography shaped opportunity. Of our 196 soldiers, 85 settled in Massachusetts and 57 in New York—these two states alone accounted for over 70% of the men we've tracked.

That geographic concentration explains a lot about what work they found.

The Laborers

Nearly 4 in 10—39%—were simply listed as "laborers." Fifty-seven men with no specific trade noted. No particular skill recorded. Just their backs, their arms, and their willingness to do whatever work America demanded.

They dug canals. They laid railroad tracks. They hauled cargo on the docks. Railroad construction was so dangerous it was said there was "an Irishman buried under every tie." In New York City, nearly 70% of Irish men* were employed as unskilled laborers—backbreaking, dangerous work that native-born Americans refused.

The Irish took it anyway. They had no choice.

The Boot and Shoe Men: Massachusetts' Gift

After laborers, the next largest group were bootmakers—22 men, representing 14.9% of those with known occupations. Add in the one man listed as "shoe shop" and you have 23 men, over 15%, working in footwear.

This wasn't coincidence. This was Massachusetts.

By 1860, approximately 50,000 people worked in Massachusetts' boot and shoe industry. The state had become America's footwear capital, with factories in Lynn, Haverhill, and dozens of smaller towns churning out millions of pairs of boots and shoes annually. Irish immigrants flooded into these manufacturing centers, finding work that—while still demanding—offered something better than hauling stone or digging ditches.

With 84 of our soldiers from Massachusetts, it makes perfect sense that boot making would be their second-largest occupation. They went where the work was. And in Massachusetts, the work was boots.

The Full Roster: Thirty-Seven Ways to Make a Living

The complete breakdown reveals just how diverse—and how humble—these men's occupations were:

The Big Categories:

-

57 Laborers (39%) - The backbone

-

22 Bootmakers (14.5%) - Massachusetts' specialty

-

8 Farmers (5.5%) - Men who'd found land

-

7 Tailors (4.8%) - Skilled needlework

-

7 Teamsters (4.8%) - Driving horses and wagons

The Tradesmen (3 or fewer each):

-

4 Stonemasons, 3 Block layers, 3 Moulders, 3 Painters

-

3 Clerks, 2 Drivers, 2 Sailors, 2 Tinsmiths, 2 Waiters

One of Everything Else (21 unique occupations with a single practitioner each):

From bakers to blacksmiths, boatmen to butchers, carpenters to confectioners, coopers to coachmen. One man was a jailor. One was a junk dealer. One worked as a roller in a mill.

One was a miner. One man spun thread, another carded wool.

Thirty-seven different ways to earn bread in 1860s America. And 57 men whose only listed skill was "laborer."

The Artisan Advantage—Thanks to Massachusetts

Here's where geography really mattered.

When we break down these occupations by socioeconomic status, artisans—skilled tradesmen—represented almost 41% of our Leitrim soldiers. That's significantly higher than the broader Irish immigrant population in places like New York, where unskilled labor dominated even more heavily.

Why? Massachusetts' boot and shoe industry.

Those 22 bootmakers (plus related trades like the tailor contingent) pushed Leitrim's artisan numbers up. These weren't just "laborers"—these were skilled workers who'd learned a trade, either back in Ireland or through apprenticeship in American factories. They used specialized tools, worked with patterns, understood leather and construction. In the rigid hierarchy of 1860s working-class life, this mattered.

Combined with unskilled workers, these two categories—laborers and artisans—encompassed 96% of the men whose occupations we know. The remaining 4%? 3 clerks, a jailor, a fireman and a confectioner represented the thin upper crust of Leitrim's Civil War soldiers.

Lower Than Low: How Leitrim Men Compared

Here's where it gets stark.

When we compare our Leitrim soldiers to Tyler Anbinder's* research on "Famine Irish" immigrants in New York, our men occupied notably lower rungs on the socioeconomic ladder. Only 3.4% of Leitrim soldiers belonged to the upper three socioeconomic categories—merchants, clerks, professionals.

Their broader Irish peers? 16.6%.

Think about that. Leitrim men were poorer than poor Irish immigrants. They came from Ireland's poorest county and found themselves at the bottom even among those who'd fled the Famine.

The one category where Leitrim men exceeded their peers? Artisans. That 40.5% figure—boosted significantly by the Massachusetts boot and shoe industry—was actually higher than the broader Irish immigrant population. Without Massachusetts' factories, that number would have been far lower, and Leitrim's soldiers would have looked even more economically desperate.

Item | Category | Leitrim Men | Leitrim % of Total | Famine Irish New Yorkers * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

1 | Professionals Doctors and Lawyers | 0 | 0.0% | 0.7% |

2 | Business Owners | 0 | 0.0% | 5.0% |

3 | Clerks, Civil Servants | 5 | 3.4% | 10.9% |

4 | Artisans | 60 | 40.5% | 32.8% |

5 | Peddlers | 1 | 0.7% | 5.0% |

6 | Unskilled workers | 82 | 55.4% | 45.7% |

145 | 100.0% | 100.0% |

*Anbinder, Tyler. Plentiful Country: The Great Potato Famine and the Making of Irish New York.

What This Tells Us

These occupational patterns reveal something profound about who enlisted and why.

Many Irish turned to the U.S. military as an employment option, recognizing that a consistent military paycheck would be invaluable in supporting their families. For the 57 men listed as laborers—with no trade, no particular skill, no way up—military service offered something attractive: steady pay, a pension if disabled, support for families if killed.

For the bootmakers in Massachusetts, military service meant leaving factory work for army life. For the farmers, it meant abandoning land they'd finally obtained. For the teamsters, it meant giving up their wagons and horses. These men joined for other reasons other than steady pay motivated by a reognition that the land that had given them opportunity needed them now in its hour of need. They believed in a republic and believed it was worth fighting for. The Civil War gave them a chance to do dangerous work with dignity, to prove their worth to their adopted country, and to earn benefits their children might build upon.

The Hidden Story in the Numbers

What the records don't capture: the discrimination these men faced.

Irish workers in northern cities were compared to Black Americans and nativist newspapers portrayed them with ape-like features. "No Irish Need Apply" signs greeted them at factory gates. Their Catholic faith marked them as foreign, suspicious, un-American.

The Know-Nothing Party rose to power in the 1850s on pure anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic hatred. They won elections. They passed laws. They made life hell for Irish workers.

Yet these men worked. They built America's railroads and canals. They made America's boots. They hauled America's cargo. And when their adopted country went to war, they put on the blue uniform and marched to the sound of guns.

The men from Leitrim—that poorest of Irish counties—came to America at the bottom. The lucky ones found work in Massachusetts' boot factories. The unlucky ones stayed laborers forever. But they sent their wages home to starving families. They raised children who'd climb higher.

And 196 of them fought in America's bloodiest war.

*Anbinder, Tyler. Plentiful Country: The Great Potato Famine and the Making of Irish New York.